KATY PINKE

hope)is st anding st.ar

Opening Reception

Reception: Tuesday, February 10th, 2026 | 6 PM

Pinke will perform a puppet show and music at the opening and closing receptions

February 10th and February 19th at 7 PM, 2026.

Exhibition Dates: February 10 - 19th, 2026

RSVP:info@kateohgallery.com

Past Exhibitions

30th January-7th February

“A Utopian World Beyond Reality”

by Kim In Ok

Date: January 8th-18th, 2026

Reception: Friday, January 9th, 6-8PM

Kim In Ok’s philosophy of slowness emerges through the motif of waiting, inspired by her repeated journeys between Seoul and her studio in Hanggeum-ri, Yangpyeong. Trains and buses appear as quiet symbols of suspended time, moving gently across open plains beyond rhythmic rows of trees. Her landscapes distill nature into simplified forms, circles and triangles refined through decades of practice, transforming memory and emotion into symbolic clarity. Small houses beneath towering trees suggest imagined worlds shaped by innocence and introspection. Rather than depicting specific places, Waiting and The Road to Hanggeum-ri offer contemplative spaces of softened nostalgia, inviting viewers into moments of quiet reflection.

by S, Alexander, Ph.D., is an art historian, poet, and curator, with writings featured in Frieze New York, The Armory Show, Skira Editore, and on Jenny Holzer.

and Yoon Jin-sup

Jin Ok Ye’s ceramic vessels—ranging from molten gold–lapped pearlescent forms to charcoal-black containers adorned with gilt wings, mosaic fragments, and celadon-tinged glazes—demonstrate her exceptional mastery of form, color, and materiality, uniting sensuous surfaces, sculptural abstraction, and deeply considered palette choices into a formalist practice that animates each piece with both organic vitality and luminous visual depth.

- By Ekin Erkan, the philosopher and art history researcher whose writing has appeared in The British Journal of Aesthetics, Philosophia, and the Journal of Value Inquiry, amongst other venues. Erkan also is an art critic who contributes to the Brooklyn Rail.

“Contemplating Hanok”, New York

by Ban Gwang-Cheon

-Exhibition of Photos of National Intangible Cultural

Property Daemokjang (Master Carpenter)

-UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage Desination (2010)

-Cultural Heritage Repair Technician (Daemokjang).

Dates: November 25th - December 7th, 2025

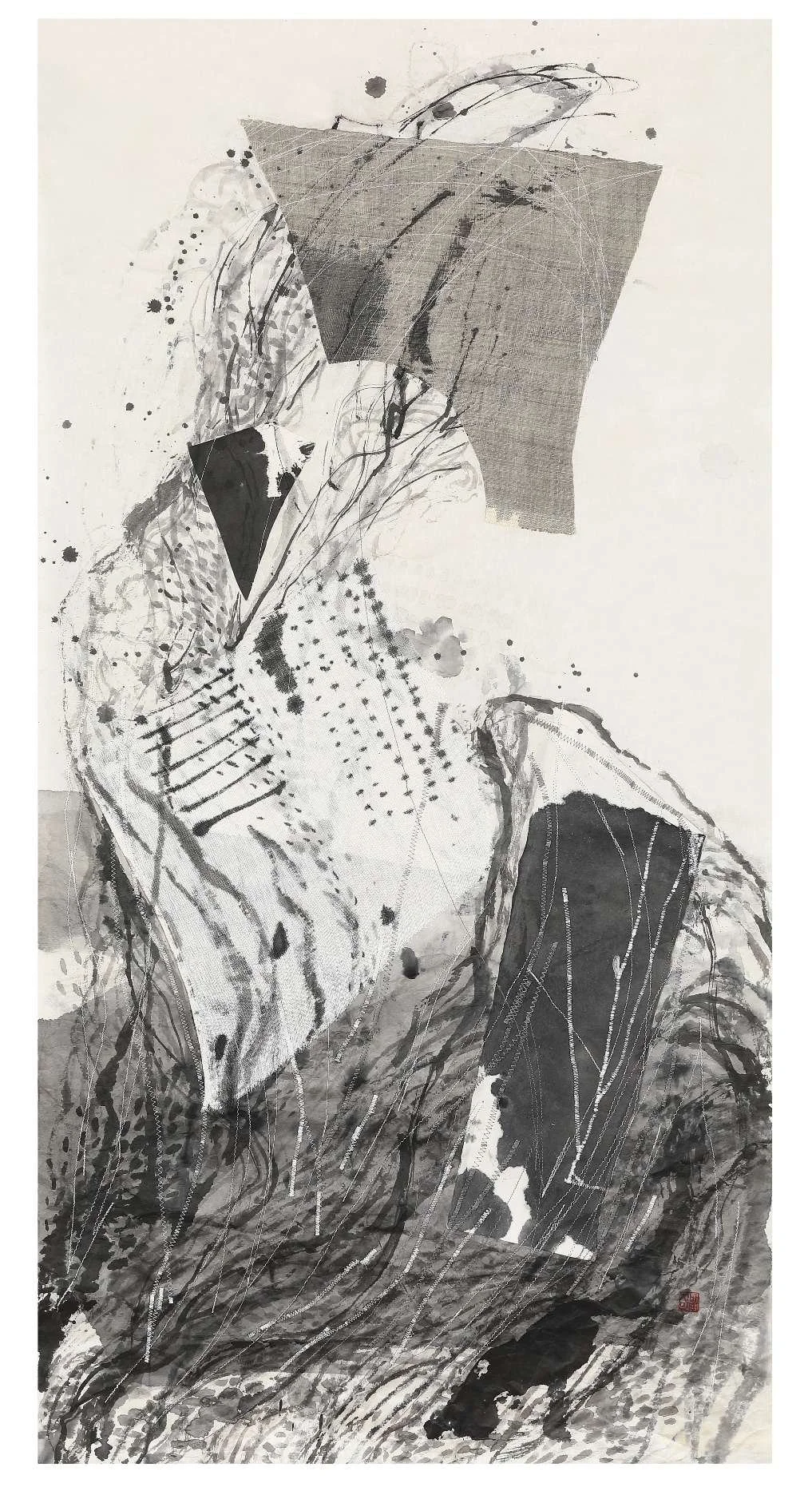

“Now & Here : SUMUK

by Jimin Bae

Dates: November 4 - 9, 2025

Reception: November 6, 5-8PM

Jimin Bae’s works recall a modernist reimagining of ukiyo-e and sumuk traditions. Her use of ink and white pigment on handmade hanji paper evokes snow laden fields and luminous skies while drawing on Korean paper arts such as jong-i jogakbo, jong-i jiseung, and hanji calligraphy. Through layering and lacquering, Bae reveals the quiet pulse of hanji itself what she calls “a natural law,” explaining, “When I touch hanji, it feels like my own skin.”

In works like Nocturnal Light and Urban Echo on a Wintry Hill, architectural silhouettes and abstract ink washes merge into atmospheric tension skyscrapers dissolve into mist while charcoal threads and soft rectangles flicker between depth and surface. Bae’s process, grounded in the traditional flow of water and ink permeating paper fibers, transforms urban forms into poetic meditations on memory and place.

Through pieces such as Still Rooted, Yet Rising and The Island’s Lonely Pole, Bae continues to explore the boundaries between presence and absence, the city and the self rendering the landscape of modern life as both familiar and dreamlike.

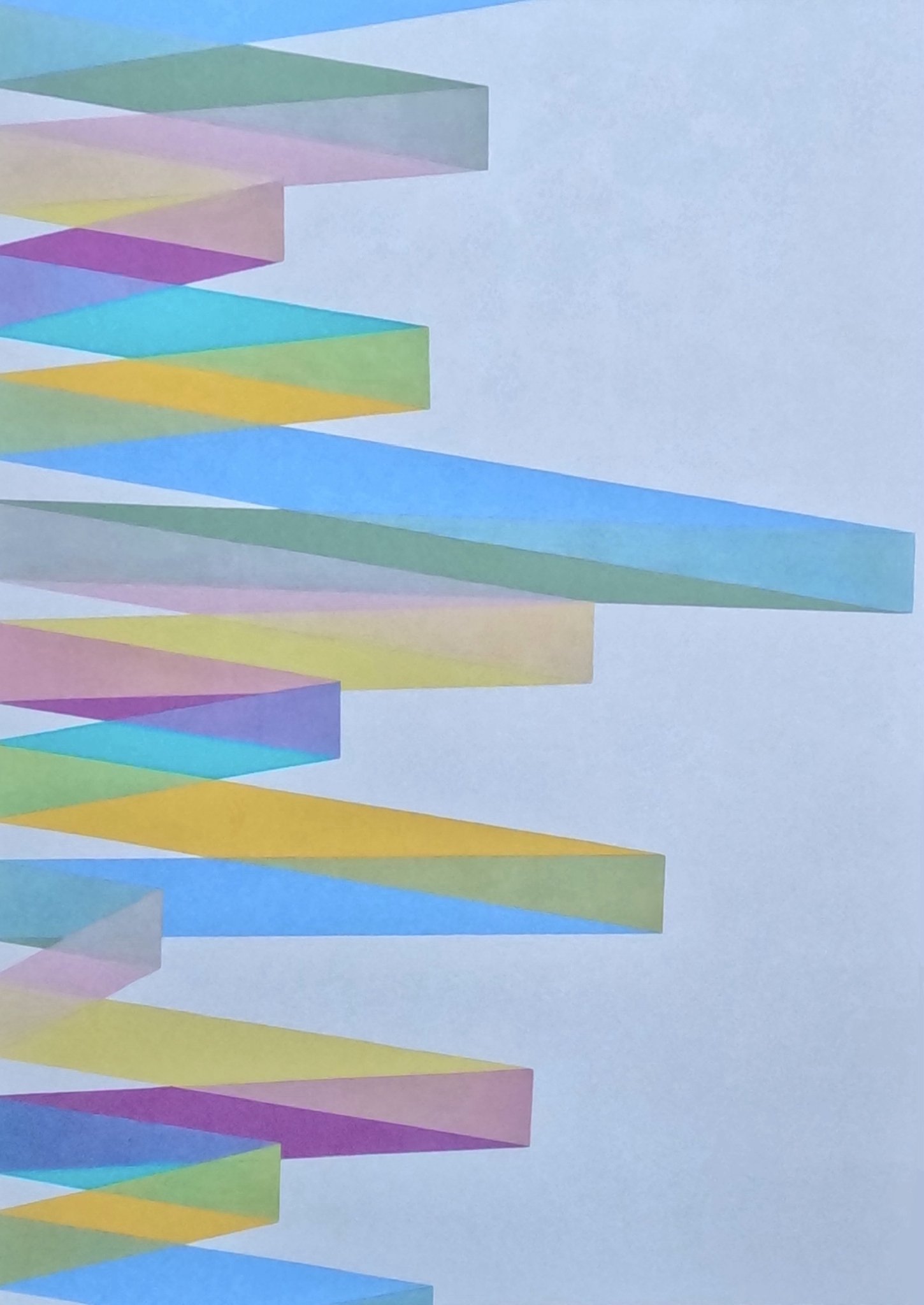

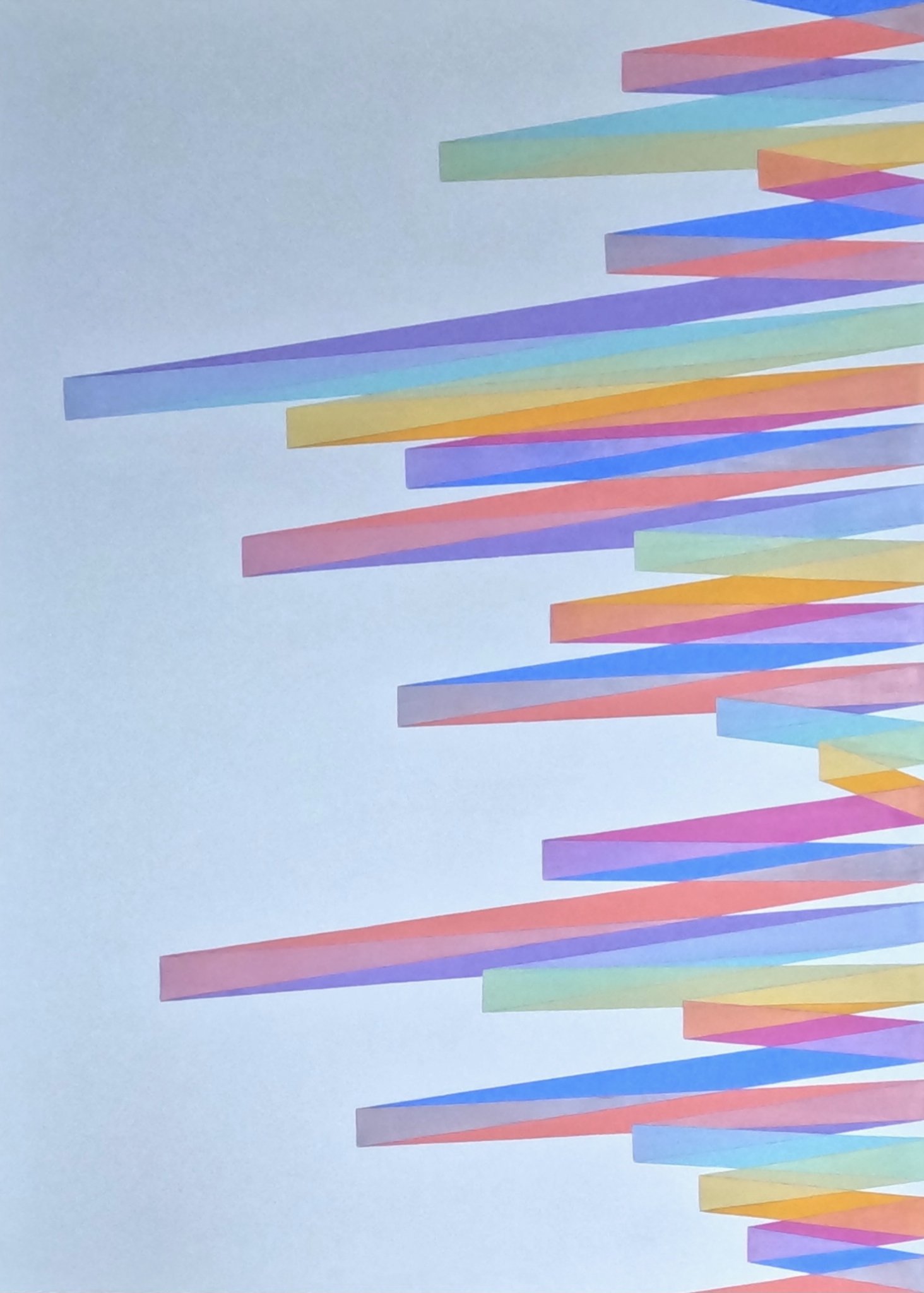

Kate Oh Gallery is honored to present “Light, Nature, Our Lives”, a solo exhibition in Upper East side New York by artist Yeong-Hi Paik.

Paik Yeong-Hi’s canvases radiate with luminous color and poised geometry, the result of a patient gaze upon nature. At first encounter, they seem free of solemn messages; yet within their quiet harmonies, a more intimate revelation unfolds. Rectilinear peaks, clouds fractured like sculptural shards, circles traced as if to summon the sun and moon, and repeated fragments arranged in rhythmic constellations-all form a personal cosmology. Her paintings weave together threads of Korean modernism: the rigor of geometric abstraction, the radiant palette partially inherited from her teacher, the late Cheon Kyungia, and a whisper of Surrealist wonder. In this fusion, Paik offers not only a transformed vision of nature but also a subtle self-portrait, refracted through light, form, and memory. Paik’s paintings extend far beyond a formalist exercise in modernism. Trained first in East Asian traditional art and later immersed in Western modernism at the Corcoran School of Arts and Design, she infuses her work with the meditative restraint of classical landscape painting, where silence itself becomes a compositional element. Beneath luminous fields of color and crystalline geometry lies a hidden code of transcultural identity. Mountains and light central motifs for many Korean artists since the myth of Dangun and long associated with national identity and spiritual energy— are reimagined in her practice. Paik’s mountains, however, are not confined to regional landscapes; they appear almost transcendental, rising beyond geography to suggest universal ideals of harmony and peace.

by Jung-Sil Lee, Ph.D. (George Washington University)

In other works, the artist advances her observations as a geometer of life. To view the world through the lens of geometry is always a precarious project. Elementary geometry treats objects as eternal and unchanging--Platonic representations of an immortal world of forms of which our earthly paradise is merely a hollow shadow. But Paik at her best seems to propose an alternative argument. For across her compositions, even the most static shapes appear dynamic via the combination of colors like the carrier of an intangible flow. And it’s this flow, itself a geometricized rendition of worldliness, that points to something higher, namely, memory.

by Benji Alexander, Ph.D., art historian, poet, and curator, with writings featured in Frieze New York, The Armory Show, Skira Editore

Yeong-Hi Paik’s recent canvases present a minimal yet distinctive style, composed of triangular shards that evoke stained glass. These prismatic fragments, set against air and light, merge into coherent structures that reveal harmony within purposeful fragmentation.

by Ekin Erkan, Ph.D, art critic philosopher and art history researcher

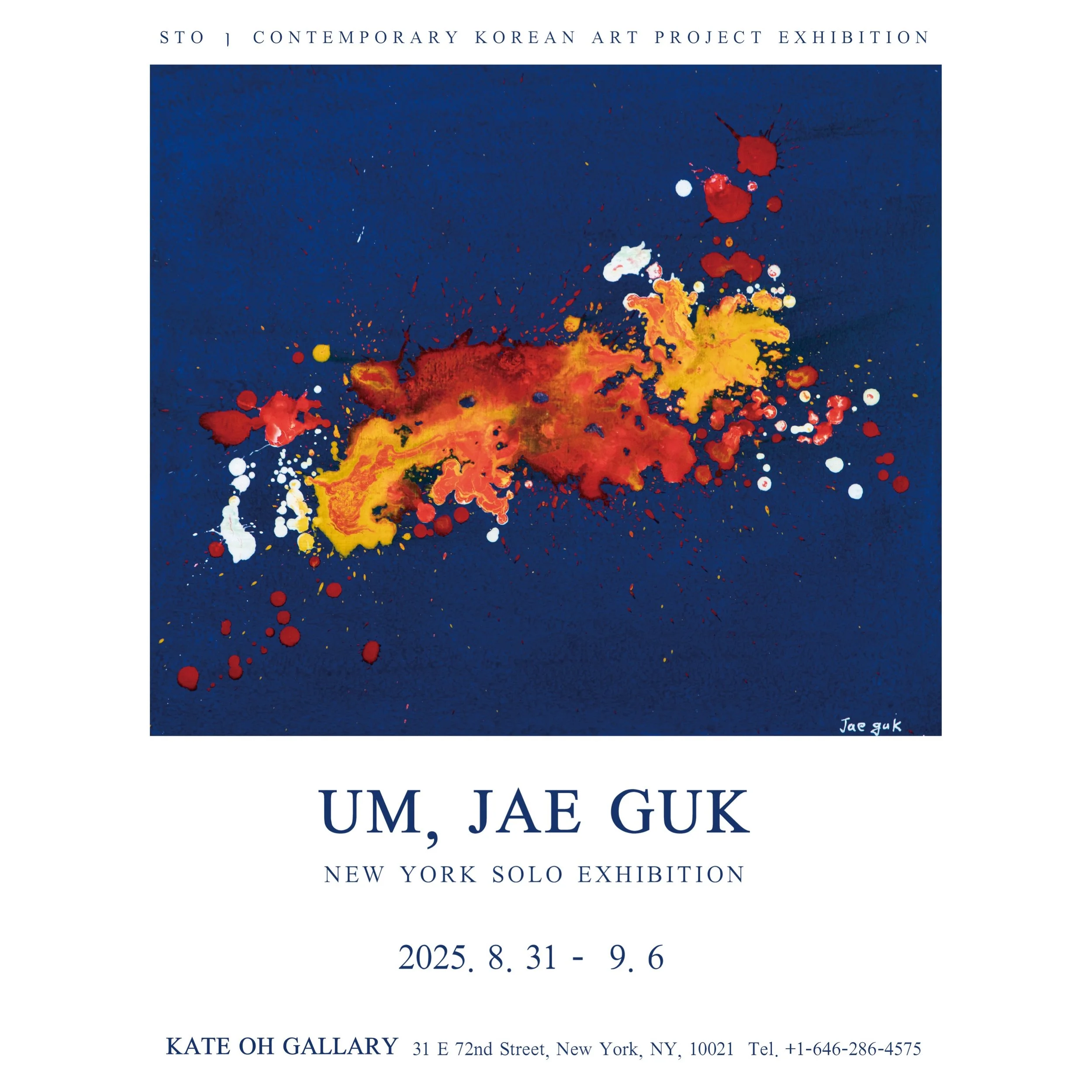

Kate Oh Gallery is pleased to present Ludens Art, a solo exhibition by acclaimed Korean conceptual artist Um, Jae-guk, on view from August 31 to Sep-tember 6, 2025, in New York.Um’s practice dismantles and reimagines the essence of art through the lens of “play,” merging painting, sculpture, and performance into a dynamic, partici-patory experience.

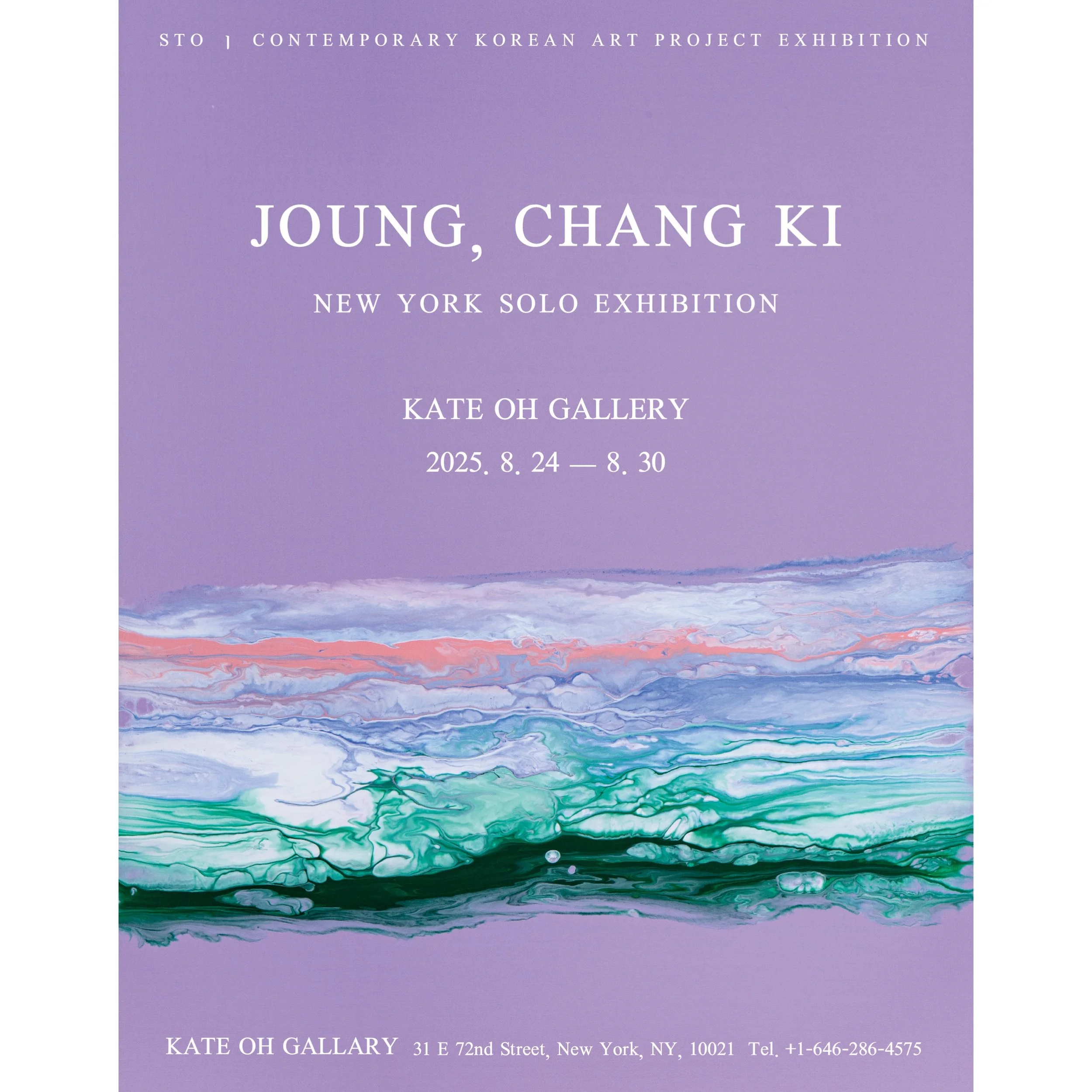

Exhibition Dates: August 24 - 30, 2025

Opening reception : August 24, at 3-5Pm

“Echoes of Light”

Dates: August 7- 22, 2025

Anay Nagawang Chodak, Angels Grau, Changha Hwang, Chi Gyu Kwon, Gyongmin Kim, Kate Oh, Kristine Virsis, Kwangsik Jung, Kwan Jin Oh, Laetitia Guyon, Sia Sangbok Lee, Rainy Tang, Sunhee Yang, Stephanie Kim

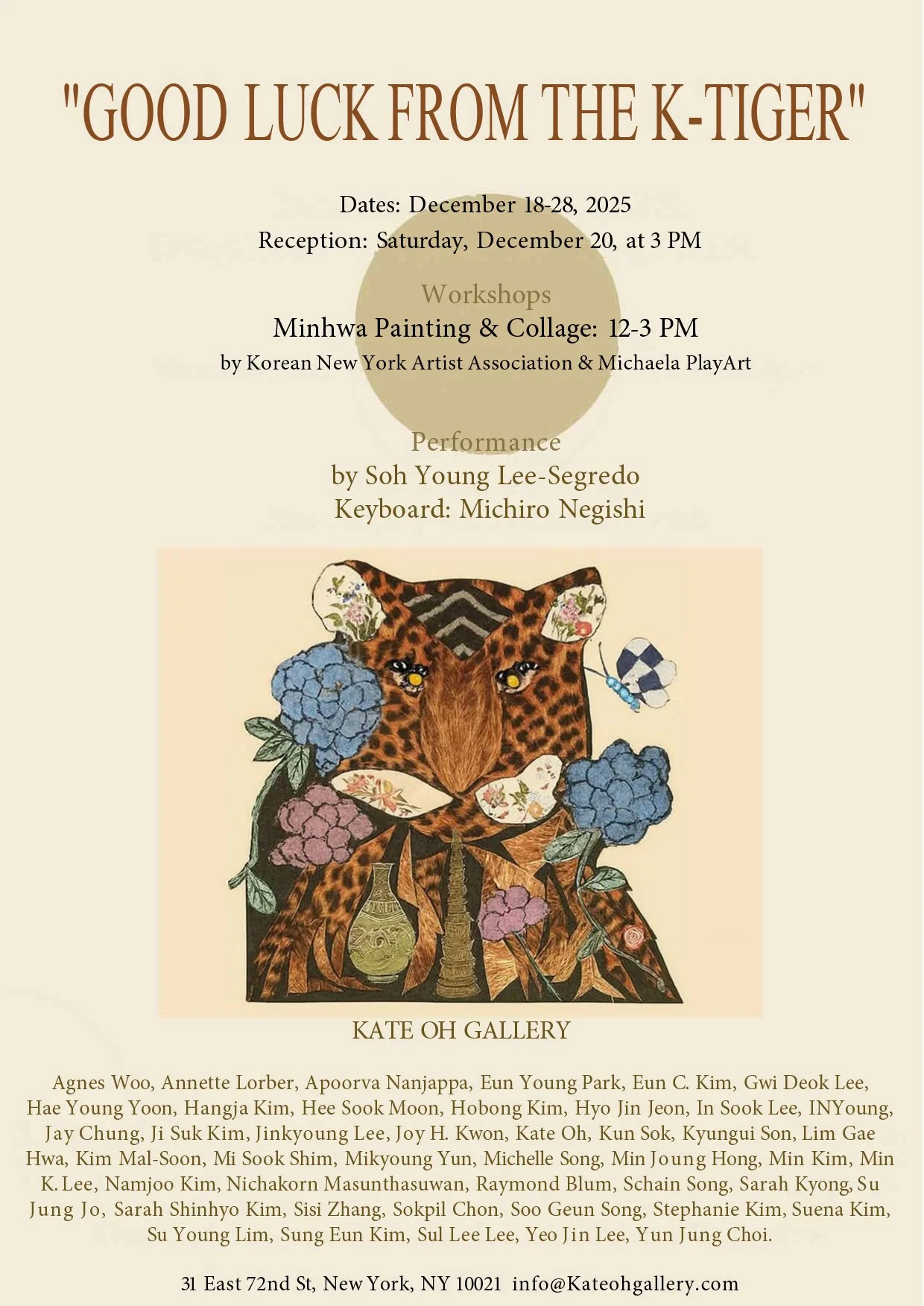

The Sun, Moon, and Five Peaks by Kate Oh

Kate welcomes K-Pop and Demon Hunter enthusiasts to the Kate Oh gallery, where magpie-and-tiger paintings along with The Sun, Moon, and Five peaks works featured in Demon Hunter are on display.

Please join ue in celebrating the art of Korean Minhwa painting.

“Hello My Name Is”

By Changha Hwang

Exhibition Dates: July 24th-August 2nd (August 3rd-7th appointment only)

Opening Reception: July 24th, 5 - 8 PM

New York-based artist Changha Hwang's recent paintings are rich with pixelated, geometric patterns that reflect a distinctly digital aesthetic. While his earlier work featured skeletal lattices, his newer pieces present layered, filled-in forms that evoke digital networks and visual noise. Art critic Pierre Sterckx observes that Hwang’s work appears to emerge from computer manipulation and mirrors the technological environments we now inhabit.

These paintings metaphorically explore how digital life shapes perception and behavior, shifting from a once-liberating, anonymous internet to a domain increasingly defined by surveillance and control. Through visually dense, partially obscured compositions, Hwang captures the complexity of digital existence, networked identity, and the tension between visibility and opacity in the age of Big Data.

by Ekin Erkan

Ekin Erkan is a philosopher and art history researcher whose writing has appeared in The British Journal of Aesthetics, Philosophia, and the Journal of Value Inquiry, amongst other venues. Erkan also is an art critic who contributes to the Brooklyn Rail.

Winsor Birchltd are delighted to announce a landmark exhibition of

Henry Orlik’s American paintings and drawings at the Kate Oh Gallery

Dates: June 17 to 29, 2025

THE NEW YORKER

One afternoon in February of 2024, Grant Ford, an art adviser and dealer in the English town of Marlborough, received a phone call from a local lawyer named David J. Goldsmith. Goldsmith wanted advice about a case involving an elderly painter, who had been evicted from his apartment in London. The painter, Henry Orlik, claimed to have lost hundreds of paintings during the eviction, which had taken place while he was in the hospital, recovering from a stroke. Orlik, who was seventy-seven, was in poor health and desperate to get his pictures back. Goldsmith needed to know what the paintings might be worth.

Goldsmith’s office, on Marlborough’s high street, is around the corner from Ford’s gallery. For thirty years, until 2016, Ford had worked for Sotheby’s, the auction house, as an auctioneer and a specialist in British and Irish art, before setting up his own business. He also appears on the BBC’s “Antiques Roadshow.” “By that stage, you kind of think you know it all,” Ford told me. He headed over to Goldsmith’s office, where Jan Pietruszka, a friend of Orlik’s family, had brought around ten pictures. The canvases were propped up on filing cabinets and leaning against a wall.

Ford was struck immediately by the paintings’ eerie intensity and control. “I was thinking, Why haven’t I heard of this artist?” Ford said. The work seemed to belong to Britain’s mid-twentieth-century movement of Surrealist art, which included painters such as John Armstrong, Conroy Maddox, and Ithell Colquhoun. But Ford was drawn to Orlik’s obsessive method: layer upon layer of different-colored hairlike brushstrokes, in acrylic, which together created a sense of dizzying detail. “I was thinking, Well, these are quite like John Armstrong, but actually they’re better than John Armstrong,” Ford said. “He’s actually much, much better than all of that.” One Orlik canvas, called “Don’t Vote,” from 1974, suggested a desolate stage at a political rally, complete with balloons, loudspeakers, and flags, under a sky of golden halo-shaped clouds. The scene rests on a heap of strange, luscious plants.

When Ford returned to his gallery, he entered Orlik’s name into Artnet, the art-price database. His search yielded barely any results. According to Pietruszka, Orlik had exhibited his work in the seventies and early eighties before turning his back on the art market, though he continued to paint prolifically in his home, a one-bedroom flat in Kensington. For decades, Orlik was financially supported by his parents, who were factory workers in Swindon. But they died around the turn of the century. After some digging, Ford eventually turned up a catalogue from a solo exhibition of Orlik’s paintings at Acoris, a Surrealist gallery in Mayfair, from 1972, when he was twenty-five years old. At the time, Acoris was selling work by Paul Delvaux, René Magritte, and Francis Picabia. “It was extraordinary,” Ford said. “He literally put his middle finger up at the art world.”

A few weeks later, Pietruszka took Ford to meet Orlik. The artist was living in his parents’ old house, in Swindon, where he was largely confined to a hospital bed on the ground floor. In two rooms upstairs, there were hundreds of works: from art-school sketches and preparatory crayon drawings to large-scale, fully realized paintings that had taken Orlik months to complete. A few canvases were framed, others were stretched, but most were rolled up inside tall cardboard tubes, dozens of which lay against a wall. Some tubes carried postage stamps from forty years earlier. “It was like finding a lost time capsule,” Ford told me. There was a bookcase stuffed with catalogues of works by Goya and other Surrealists, along with books about Stanisław Wyspiański, a Polish modernist painter, and about Hitler’s army. (Orlik’s parents were refugees from Poland and Belarus; he was born in a camp for displaced persons, in Germany, in 1947.) Almost all the paintings demonstrated Orlik’s distinctive, coiled brushstrokes—which he calls “excitations”—a method that he developed when he was twenty-three.

Ford was convinced that some of the works belonged in a museum. But Orlik was unknown. He hadn’t sold a picture for forty years, and this made it extremely difficult to put a value on the paintings he had lost. (According to Southern Housing, Orlik’s former landlord, all the belongings in his London apartment were “disposed of” while he was hospitalized, in early 2023.) In order to establish a market rate for Orlik’s work, Ford proposed an exhibition at a friend’s gallery, in London. “I said, ‘If we’re going to stand up in court and put a valuation on the missing pictures, then actually we need evidence,’ ” Ford recalled.

Last August, five days before the show opened, the Guardian published a news story about Orlik’s rediscovery. Ford was on his way back from Belfast, where he had been filming an episode of “Antiques Roadshow,” when his phone began to light up. “Literally, we were getting two e-mails every ten minutes for twenty-four hours saying, ‘We want to buy a picture by Henry Orlik,’ ” he said. “They all went before the doors even opened.” One large painting, “Cannon Balloons,” sold for thirty-five thousand pounds. A second, smaller show—at Ford’s gallery, in Marlborough—sold out as well.

In the past eleven months, Orlik’s paintings have earned more than two million pounds. During the same period, Ford and a researcher, Sara Clemence, have attempted to piece together the story of Orlik’s life and career. (A desktop computer containing a detailed catalogue of Orlik’s output was lost during his eviction.) Some of the information has come from Orlik himself. “He’s pretty fragile,” Ford told me. “We don’t know how long we’ve got him for.” One chapter of Orlik’s life reads as a particular turning point. In 1980, he moved to New York, where he lived and painted for four years—trying, unsuccessfully, to establish himself as an artist. Forty years after he left, a show of Orlik’s paintings made during that period, “Surreal Metropolis: Looking for America,” has opened at the Kate Oh Gallery, on East Seventy-second Street.

Afew weeks ago, I drove to Marlborough to see Orlik’s paintings before they were shipped to New York. It was early on a Sunday morning, and Ford had arranged them in the corridor of a warehouse on the edge of town. Up close, Orlik’s excitations have a mesmerizing, machinelike quality—alive and detached at the same time. “I need to animate the surface of the picture to express the dialogue that I conduct with whatever I observe and the way it moves my spirit,” Orlik wrote in a document about his work, in 1994, which Pietruszka uncovered last December. Orlik calls his method quantum painting—an attempt to depict both the outer and the inner, subatomic life of things. “The materialist culture denies the existence of the invisible even though the inner is all there is,” Orlik wrote. “The outer is a garment, a mask. That is why today the world belongs to those without an inner life, the bandits.”

At first, Ford was nervous about working with an artist who had once forsaken people like him. “Knowing the history that he hated greedy dealers and agents,” he said, “I was, like, Well, actually, I don’t want anyone to be too angry with me.” It was only very recently that Ford learned that Orlik’s main dealer in the seventies was an actual bandit. The owner of the Acoris gallery went by the name Anton von Kassel and told people that he was Bavarian royalty. In fact, he was a Greek swindler whose birth name was Antonios Hatzinestoros. In the late seventies, von Kassel went bankrupt. In 1991, he was sentenced to six years’ imprisonment for tricking a British bank out of three million pounds before absconding to a French château.

According to Ford and Clemence’s research, Orlik moved to the U.S. in early 1980, after he sold four pictures to Beverly Coburn, the wife of James Coburn, the Hollywood actor. Orlik stayed in Los Angeles for a while before moving to a commune in San Raphael, near Sausalito, and arrived in New York toward the end of the year. His work became more animated after he moved to the city. The excitations became freer and more expressive. One of Orlik’s large New York paintings, “Winos in Central Park,” shows a couple of figures, transmogrified into musical notes, looming out of the night. In other paintings, the city stumbles upward, taking the form of metal clouds. A self-portrait, titled “Cyclops,” resembles a towering, head-shaped edifice, on the point of explosion.

Orlik didn’t get along with New York. He found the people rude and aggressive. He was rejected by gallery after gallery. “You see him coming back to his studio, and you get a much darker, more ferocious palette,” Ford said. “It’s almost a bit of an anger from the bluntness of New York.” But there were quieter, more beautiful paintings, too—filled with Orlik’s odd, occasionally prophetic imagination. “Wall Street, New York City” is a straightforwardly uplifting view from Orlik’s apartment window: a city of excitations, etched through with the dead-straight lines of metalwork and balconies. “Totem,” which he painted between 1982 and 1984, shows a space shuttle crashing and taking off at the same time, in a valley of billowing folds. “There’s almost the element of body parts within these curves,” Ford said, leaning close to the canvas. “I mean, you see all sorts of things in his pictures.”

Orlik used to go and sit in Central Park every day. “Everything else was cement, and that was unreal,” he told me one afternoon in late May. “It was all made up by intellect. But nature was Central Park, and that was very important.” Orlik was sitting up in his hospital bed, in the front room of the house in Swindon, wearing a yellow T-shirt under a dark cardigan. Pietruszka and Ford were there, too. A portrait of Orlik’s mother, Lucyna, in excitations, hung above his head. He sometimes struggled to form words, but he was otherwise lucid and alert. When I put my voice recorder down on his bedside table, Orlik produced one of his own, out of a glasses case containing a piece of paper with the word “stroke” written on it, and carefully turned it on. He didn’t say why. He had messy, white, tightly curled hair and bright-blue eyes. The iris of his left eye had a white bar across it, like a horizon line. I asked him if he remembered feeling isolated in New York. “No, because I never felt anybody really understood my work,” he said. “So it’s always been lonely.”

Orlik initially stayed at the Benjamin Franklin hotel, on Broadway and West Seventy-seventh Street. “It was hard. Cockroaches and mice,” he said. He survived on chicken thighs. He drank a lot of wine. The skyline repelled and attracted him in equal measure. “I always saw them as living things,” Orlik said. “They were something more than just buildings—they were real moving entities.” Most of the time, he worked. Some days, Orlik painted for eighteen hours, in a fugue of constant brushstrokes. “That’s what it’s all about,” he said, of his excitations. “That’s my work, not the visual shapes but the actual movement, the marks I made.” I asked Orlik to describe the feeling of being lost in a painting. “It’s something very deep, which you may not understand,” he said. “It is more real than real life.” In 1994, he wrote, “There is an intimacy between myself and the canvas, an overlapping.”

In 1985, Orlik returned to England. With the exception of a small show in Hampstead, in 1994, he never showed his work again. “I was too different,” he said. “Success means people like me or want me. My work has nothing to do with other people. It’s to do with me, me learning about myself.” In the early nineties, Orlik signed the lease on the apartment in Kensington. It was situated in Redcliffe Square, which had artistic connections. “A Day in the Life,” the Beatles song, was inspired by a car crash there, which killed Tara Browne, an Irish socialite who had introduced Paul McCartney to LSD. Robert Lowell, the poet, was a resident in the seventies. One of the flats neighboring Orlik’s belonged to the partner of Mario Amaya, an art critic and a friend of Andy Warhol’s, who was shot alongside the artist, in 1968. Orlik used to glimpse Warhol paintings on the walls inside.

Orlik lived alone. He shopped for art supplies. He went to galleries. “Wonderful paintings,” Orlik recalled. “Nothing to do with me.” Pietruszka, who worked as a financial adviser and remained close to Orlik’s parents, remembered him bringing his work to show them. “He used to come to the office in Swindon,” Pietruszka said. “ ‘Look, this is my latest batch.’ ” In the twenty-tens, Orlik started making word paintings, in which his excitations became a form of script, which only he could read. (The computer that was lost during the eviction contained the translations; Ford is hoping to decipher the script with A.I.) He was a complicated soul. He despaired of “mechanistic Newtonian culture.” He fought with his neighbors. No one really knows how Orlik survived his stroke. It is thought that he lay on the floor of the house in Swindon for up to three days. Somehow, he reached the front door and called for help.

After about an hour of conversation with me, Orlik grew tired. He seemed tickled, more than anything else, by his eventual rediscovery. “I’m embarrassed,” he said. He nearly attended the opening of his exhibition in Marlborough last summer, before changing his mind and deciding not to leave the house. Pietruszka was stubbornly hopeful about recovering Orlik’s lost work, which consists of around a hundred and twenty canvases and some five hundred word paintings. After offering a fifty-thousand-pound reward for their return last year, Pietruszka received a tip that they had probably either been sold at a flea market in Hounslow, in West London, or been placed in a storage unit. “I think they’re stashed,” he said. The more publicity there was about Orlik’s paintings, the more likely Pietruszka thought it that they might resurface. While I talked with Orlik, Ford roamed about the house, occasionally marvelling at an old drawing or painting that he had not seen or studied properly before. Orlik watched the busy art dealer, who had finally made his name. “He’s a complete mystery,” the artist confided, full of wonder. “A mystery.” ♦

The New Yorker 100

Anay Ngawang Chodak E-Catalog:

https://heyzine.com/flip-book/f61e68df80.html

Modern Reflections of Wisdom and Compassion

by Anay Ngawang Chodak

Kate Oh Gallery presents "Modern Reflections of Wisdom and Compassion," a solo exhibition by Anay Ngawang Chodak, a contemporary artist who bridges centuries of Tibetan Buddhist tradition with the visual language of contemporary abstraction. Rooted in the refined techniques of traditional Buddhist art, Anay’s work explores the spiritual dimensions of form, color, and human inner values through motifs—his signature Happiness Pods, interconnected patterns, blossoming floral elements, and luminous color fields.

Delivering his art through contemporary visual expression, Anay creates a meaningful connection between ancient wisdom and modern life, allowing today’s audiences to engage with universal Buddhist values through a fresh, contemporary lens. This exhibition invites viewers into a vibrant, visually exquisite, meditative space where Anay Ngawang Chodak’s meditative art serves as a mirror for inner clarity, interconnectedness, and oneness.

Anay Ngawang Chodak’s work emerges as a sincere expression of inner insight, where meditation and philosophy converge in visual form, continuing to unfold and evolve within contemporary art spaces. Anay forges a meaningful connection between ancient wisdom and modern life through a contemporary visual language, offering audiences a fresh and deeply resonant means to engage with universal Buddhist values. This exhibition invites viewers into a vibrant, visually exquisite, and meditative space where Anay Ngawang Chodak’s art serves as a mirror for inner clarity, interconnectedness, and oneness.

In conjunction with the exhibition, the artist will also lead a special Meditative Art Class consisting of three immersive sessions. June 8,9 and 15th at the Kate oh gallery.

Rooted in traditional techniques and mindfulness practices, these guided workshops provide participants with an opportunity to explore the calming and introspective nature of art-making under Anay’s instruction. Advance registration is required, and a participation fee applies.

Born in 1968 in Tbilisi, Georgia, Rusudan Petviashvili’s artistry has been celebrated worldwide. Listed in “2000 Famous Persons of the 20th Century” by the Cambridge Biographical Center, Rusudan’s talent emerged early in life — her first solo exhibition took place at the remarkable age of six. Rusudan’s artworks have graced various exhibitions in notable cities such as Paris, London, Berlin, Geneva, Vienna, and Budapest. Her illustrations have also been featured in esteemed publications, including the “National Fairy Tales of Georgia” and the celebrated French edition of “The Knight in the Panther’s Skin".” Furthermore, Rusudan illustrated an exclusive handwritten New Testament with the blessing of the Georgian Patriarch, now displayed as part of the world’s largest handwritten Gospel at the Cathedral of the Holy Trinity in Tbilisi. Her works are part of private collections worldwide.

Touchable Sky

Presented by KOREANECTION

In collaboration with Buan Celadon Museum

Exhibition Dates: May 18–28, 2025

The celadon works presented in this exhibition were produced at the Buan Official Kiln in South Korea, a state-operated ceramics center during the Goryeo Dynasty. As a government-run kiln, Buan was responsible for creating high-quality wares for royal and official use, showcasing the height of celadon artistry through its refined inlay techniques and elegant jade-green glaze.

“Selective Memory” by Nevil Dwek

Kate Oh Gallery is proud to present Selective Memory, a solo exhibition by multidisciplinary New York artist Nevil Dwek, on view from May 1–17, 2025

Dwek will also host an author reading with Michelle Young for her newest book The Art Spy: The Extraordinary Untold Tale of WWII Resistance Hero Rose Valland on May 8th from 6pm – 8pm.

On May 17th, the gallery will participate in the Madison Avenue Spring Gallery Walk, where Dwek will hold an artist talk at 1pm, 2pm and 3pm.

A graduate of NYU’s Tisch School of the Arts, Dwek’s art has been exhibited internationally, including shows with The Core Club, Shrine Gallery, Artopia Consulting and Red Fox Gallery. As a professional photographer, Dwek was commissioned for bespoke projects with clients including Peter Marino, Chanel and Ralph Lauren. He also founded Dmr Productions, a film and photography company whose work has earned multiple awards

In Selective Memory, Dwek invites viewers to explore the space where memory and presence converge, where the light of now reflects the shadows of then. He uses windows as both literal and metaphorical portals, as each piece invites a return to memory through light and perception. Reflections, shifting shadows, and subtle color are more than visual elements, holding a romantic nostalgia shaped by moments that once felt more alive, more connected. What we remember depends on where we are now.

Using his personal photography archive, Dwek builds dimensional, collage-like works crafted using materials such as aluminum, mirrors, and plexiglass to create that layered, shifting world. He uses photo paper and clear film, cutting it by hand and layering it to build dimensionality and includes his writing in the pieces as well as AI tools when needed to expand and support the emotional and conceptual depth of the work. To evoke the dreamlike, shifting quality that memories often hold, Dwek adds alcohol inks andIndian inks to introduce fluid and unpredictable color in the work.

“The past in this series is not static. It flickers, fades, glows again. And through reflective materials, we glimpse how the past and present coexist, as the light and reflections stir a quiet tension between presence and memory,” said Dwek. “These reflections are not fixed. They evolve.” On May 17th, the gallery will participate in the Madison Avenue Spring Gallery Walk, where Dwek will hold an artist talk at 1pm, 2pm and 3pm.

“Wings of Joy” Exhibition Dates: April 3-18th, 2025

Pema Rinzin

Asian Art week

The Luminous Heart: Sun Hee Yang’s Multicultural Vision of Color, Pop, and Transcendence

In a city where Western art often dominates, the Kate Oh Gallery offers a fresh platform for Korean contemporary art, blending history, modernity, and spiritual depth. Sun Hee Yang’s work embodies this synthesis, merging Buddhist.

A Vessel Embracing the Universe

Sia Sang Bok Lee’s work explores organic yet abstract elements, characterized by textures and spatial dynamics centered on the interplay of light and shadow. Her creations evoke both cosmic and microscopic realms, devoid of human or animal figures, yet rich in organic forms and movements.

Often utilizing hanji paper and canvas as her base, Lee enhances visual tactility and depth, delving into the subjective quality of light. This approach resonates with Mark Rothko’s concept of "light impressionism," emphasizing light’s ability to unify space and create atmospheric tactility. Lee employs this principle to construct organic worlds where light and darkness coexist in harmonious juxtaposition.

Her works refrain from depicting literal or representational scenes, instead offering abstract, cosmic imagery that invites the viewer's interpretation. Through series such as "Cosmos" and "Relationship of Life," Lee has consistently explored organicity—creating de-peopled landscapes and abstract environments that suggest cellular or planetary phenomena.

In her recent works, Lee delves further into celestial abstraction, incorporating elements of stars and the cosmos to build worlds that transcend traditional earthly motifs. Her art masterfully balances illumination and shadow, crafting a poetic, meditative practice that highlights ripples, textures, and the quiet interplay of light. Her works, grounded in meticulous technique and thoughtful composition, invite viewers to pause and reflect, engaging deeply with the organic and the sublime.

Vibrant Perspectives: The Art of Marko Stout

Marko Stout’s newest and most exciting exhibition is launching on December 5th at the iconic Kate Oh Gallery on the Upper East Side. Expect bold colors, edgy themes, and the raw energy of urban life brought to life in Stout’s unforgettable style. Join us for an evening of art, creativity, and great company as we celebrate this highly anticipated show!

“Marko Stout is a rockstar in the art world” - RollingStone Magazine

“Marko Stout is the epitome of glamour” -

COSMOPOLITAN Magazine

Opening Night: December 5, 2024

INVITATION

Collect Brazilian Jewelry, curated by Dorine Botana, is honored to invite you to the new edition of its highly anticipated exhibition of signature jewelry, showcasing the creative talent of renowned Brazilian artists.

“ Invisible Women & Brave Girls” by Angels Grau

October 10 - November 3rd, 2024

Angels Grau Invisible Women 48x48”

Invisible Women & Brave Girls by Angles Grau

Kate Oh Gallery is delighted to present “Invisible Women & Brave Girls”, an exhibition of acrylic paintings by Àngels Grau, a Spanish artist renowned for her powerful portrayal of both physical and metaphorical strength. Inspired by her daughters, Claudia and Mafalda, this series goes beyond traditional art, offering a bold visual statement that encourages every girl to confront challenges, harness her inner strength, and transform the world.

“Brave Girls” embodies the fearless spirit of the girl who confronted the Wall Street bull, standing as a symbol of courage and resilience. These works capture the ability to rise, lift oneself up, and start again, even when everything around seems to be crumbling.

The series portrays young women who, despite being overlooked or undervalued, face life’s obstacles with heads held high and unwavering confidence. Like the girl who defied the bull of tradition and expectation, each “Brave Girl” represents the power to break down barriers, challenge societal norms, and embrace limitless possibilities. These women are not merely surviving—they are thriving and leading change.

In each painting, Grau vividly depicts the strength, passion, and talent of these young women. Her work conveys both individual stories and the collective spirit of women pushing boundaries and striving for a better world.

At the heart of this series is the message: You Can. Each painting resonates with the belief that great achievements are possible when challenges are faced with courage. “Brave Girls” is not just an art series—it’s a movement for change, inspiring young women to stand up, break barriers, and create their own futures.

“ Wanderer” by Kim Seok-Young

Dates: Oct 1-8th, 2024

“Wanderer” by Kim Seok-Young from October 1-8th, 2024

Kate Oh Gallery is thrilled to present "Wanderer" by Kim Seok-Young, the artist's 33rd solo exhibition.

Opening October 1st in New York, this show introduces Kim Seok-Young, an artist renowned for his powerful expressionist works featuring horses, flowers, and human figures. Kim's diverse practice spans painting, video, and sculpture, blending Eastern spiritual energy with contemporary artistic expressions. For his New York debut in the heart of the contemporary art world, Kim has chosen the theme "Discovery" - a journey to find oneself and our collective identity.

As Robert Morgan writes in the exhibition foreword:

"Viewers will feel a surge of 'qi' (life force) emanating from Kim's works. The artist's boundless energy release connects to the Taoist concept of 'Dao' or 'Way' - essentially a path to enlightenment. There's no set formula for this process. It's like sweeping fallen leaves on quiet temple steps - a means for something to unfold. This exhibition invites us to embark on a journey of self-discovery, asking: 'Who are we, and what are our potentials?'"

In these turbulent times of global environmental crises and conflicts, this exhibition offers a moment to reflect on and rediscover ourselves and our shared humanity.

“ Impermanent Bubbles” by Pema Rinzin

Dates: Sep 5th - 29th, 2024

Kate Oh Gallery is pleased to announce Impermanent Bubbles, the first solo show of Pema Rinzin at the gallery.

Bubbles painted with natural dyes and hand-ground mineral pigments fill up Rinzin’s canvases, wood panels, and paper works. The foamy fields are at once planar and dimensional: micro and macro; claustrophobic swarms and vast expanses.

Rinzin chose the bubble because it cannot be held. It appears shimmering before you for only a moment before it pops. Rinzin understands the main teaching of Tibetan Buddhism to be impermanence. For him, there is much to be learned from contemplating something so small and transient.

The bubble is not a new shape for Rinzin. In fact, he has been encircling color since he trained to become a master in Tibetan thangka painting. In every Tibetan thangka, there is an offering presented which represents a gem. Either yellow, blue, green, or red, it is a physical offering to the gods. But its abstract rendering reminds us that even if you have nothing material to give, there is always something to offer: a water droplet, an idea, a prayer.

Rinzin’s past bodies of work have been more figurative. For Impermanent Bubble, he was looking for a process of repetition that paralleled the chanting of a Mantra. “You don’t wear out a mantra,” says Rinzin. “You can do a mantra through all your life into your next life. Collecting one million; two million; three million.” He admits boredom can creep in during the time-consuming repetition of the painting process. But this, too, is an important part of the practice. Cycling through becoming numb, he will once again emerge into the awareness and the sweetness of his efforts.

As Rinzin developed these paintings, he noticed that the bubbles took on particular characteristics. For instance, certain color combinations caused fields of bubbles to form landscapes. Others suggested the cosmos. Still others, which he calls dropping bubbles, became worlds within world, nested and playing with scale.

“Insight and Sapience” by Erica Kim

August 13th- September 3rd, 2024

Erica Kim’s art featured at Times Square on a Billboard on August 23rd, 2024

Summer Group Exhibition

July 23- Aug 11th

Lana (Sveta) Malakhoff

Dates: July 2 - 20, 2024

Urban Wave - New York

Dates: June 4 -11, 2024

Agnes Son Exhibition

Dates: May 22 - June 2, 2024

Artist Statement

I pursue perfection again today, striving to achieve it with all my might. Yet, I despair as I feel the emptiness of unfulfilled yearning. Is realizing that nothing is perfect the destination of life? What is the standard of perfection?

Today, I torment myself in the pursuit of perfection once more. Let it go. It must be let go. Dot by dot. These form lines. Lines, lines, they reveal surfaces.

Today, hardship and happiness coexist. Perhaps everything is completed when they coexist, where even aging and novelty add depth to the canvas of life.

Is perfection the coexistence of completeness and incompleteness? Today, I meet the me of 40 years ago and face the present me. The weight cannot be measured, but all the emotions that were by my side then led the present me into anger, despair, and regret. In the end, reconciling with all those emotions, I shape the present me, leading me to tomorrow with excitement. Joyful and happy, every moment spent with my art.

Dot, Line, and Surface.

On May 18th, Kate Oh Gallery by Asher Min’s photography exhibition will be part of the “Madison Avenue Spring Gallery Walk 2024” and there will be two Gallery Talks at 2:00pm, and 4:00pm. It is FREE and OPEN TO THE PUBLIC.

Asher Min

May 8-19th, 2024

“Min’s photographs catch us in the dark, which is how he wants them to be. As expressed in “Waterfall of My Dreams”, there are three elements that constitute the subject matter in this work. They include “painting, performance, and photography.” Together, the viewer is invited to concentrate on this work as if the evening waterfalls were actually going to descend, which finally they will, prior to being caught in abstract shapes between the various limits of light that surround their depth and darkness.”

- Robert C. Morgan, art critic

Laura Manuel

Date: April 16-28, 2024

“ About Hope” Hanji, oriental paint, 56.5 x 82.5” $50,000

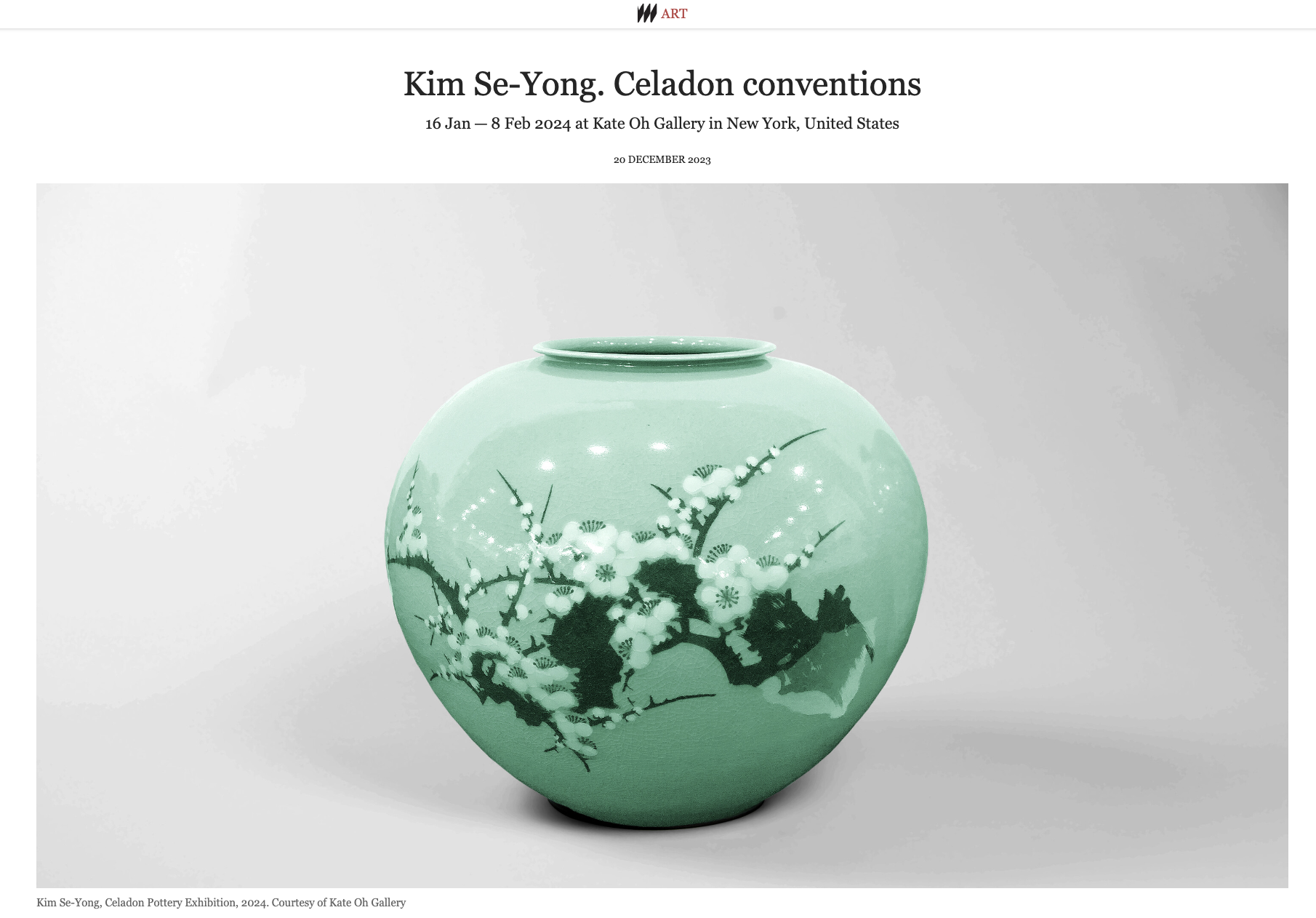

“Royal Celadons”

Exhibition Date: January 6 - March 14, 2024

By appointment only from February 9 - March 14

RSVP at info@kateohgallery.com or (646) 286-4575

https://www.meer.com/en/77588-kim-se-yong-celadon-conventions

Kate Oh Gallery - video credit to creativeAgroup

HeizleLand

December 19, 2023 - January 5, 2024

“Symphony of Opulence”

by Marko Stout

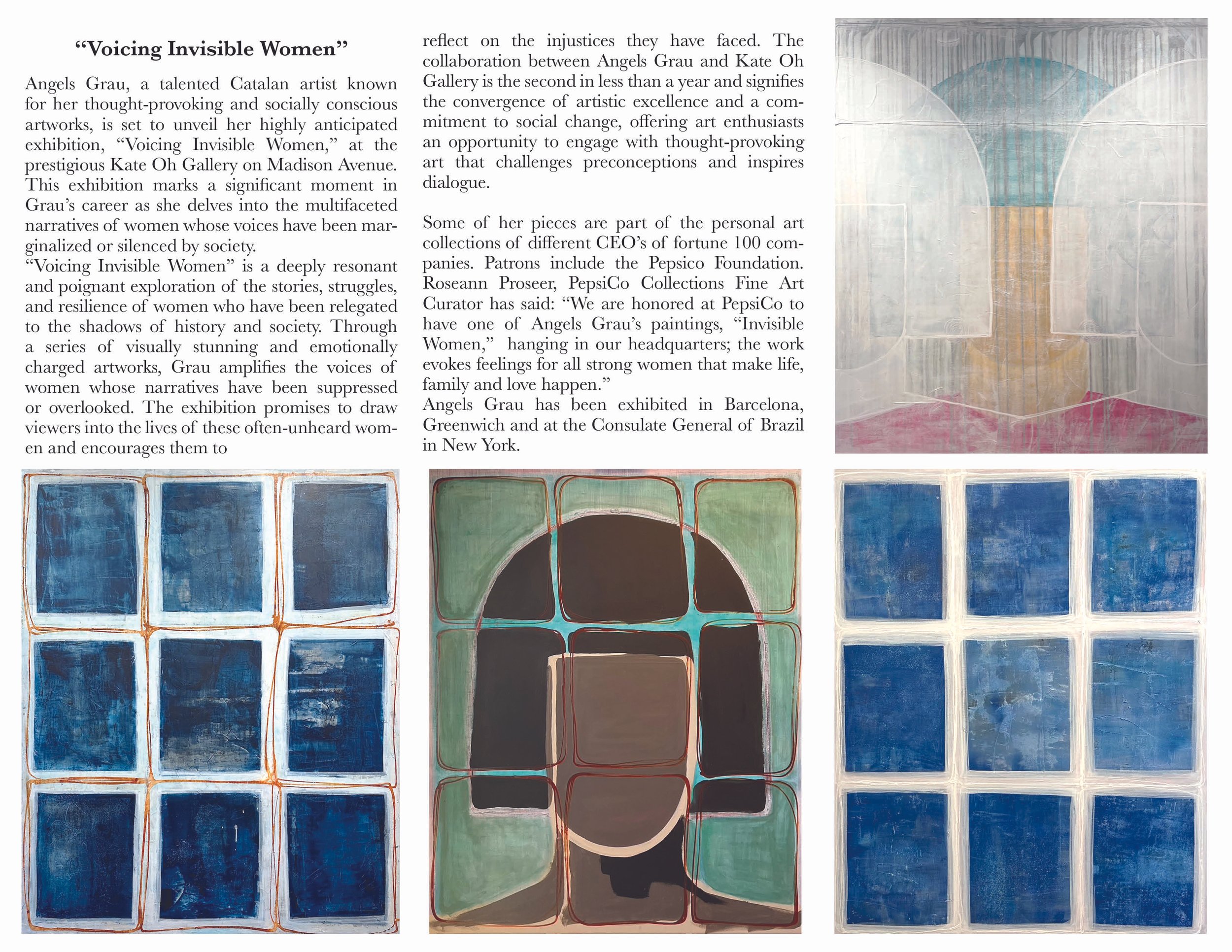

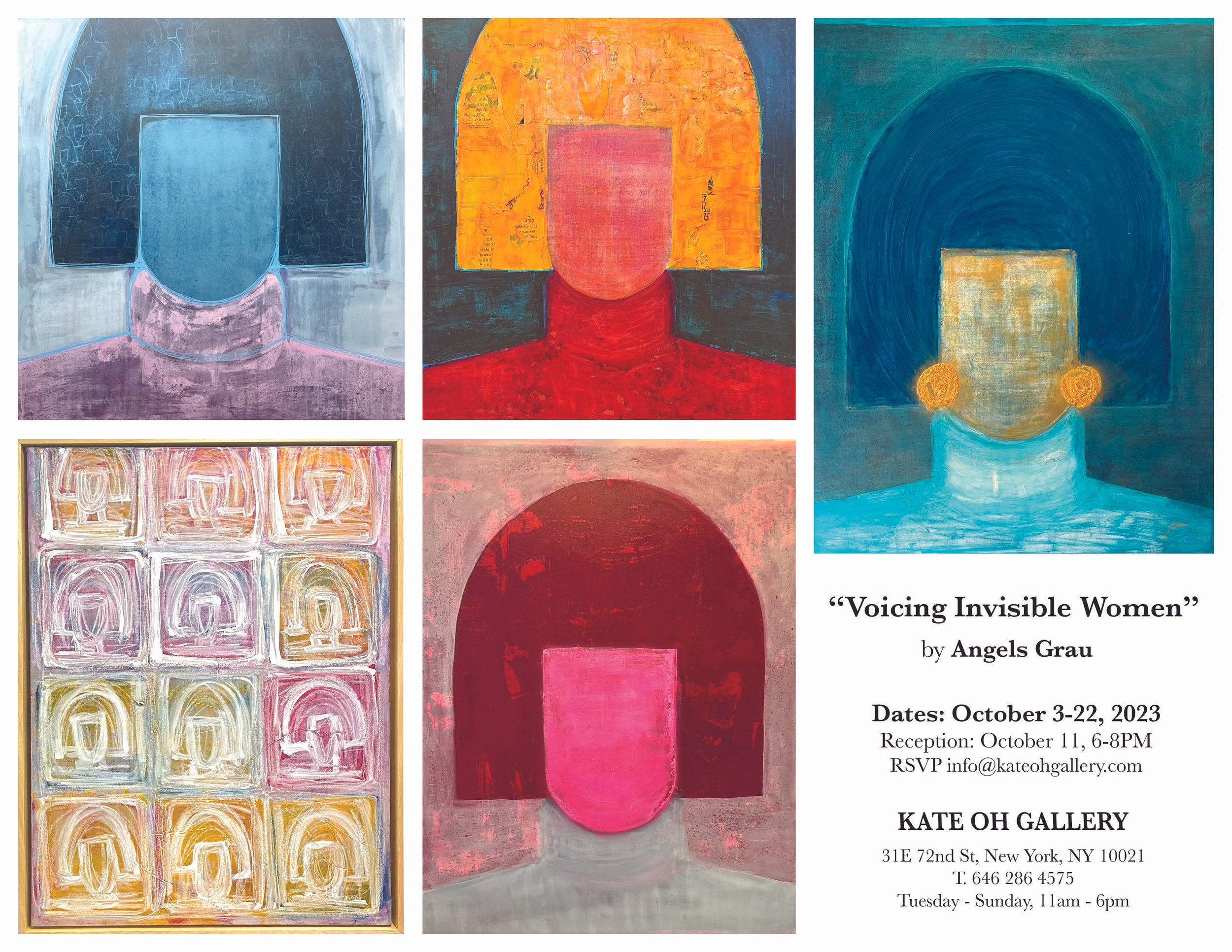

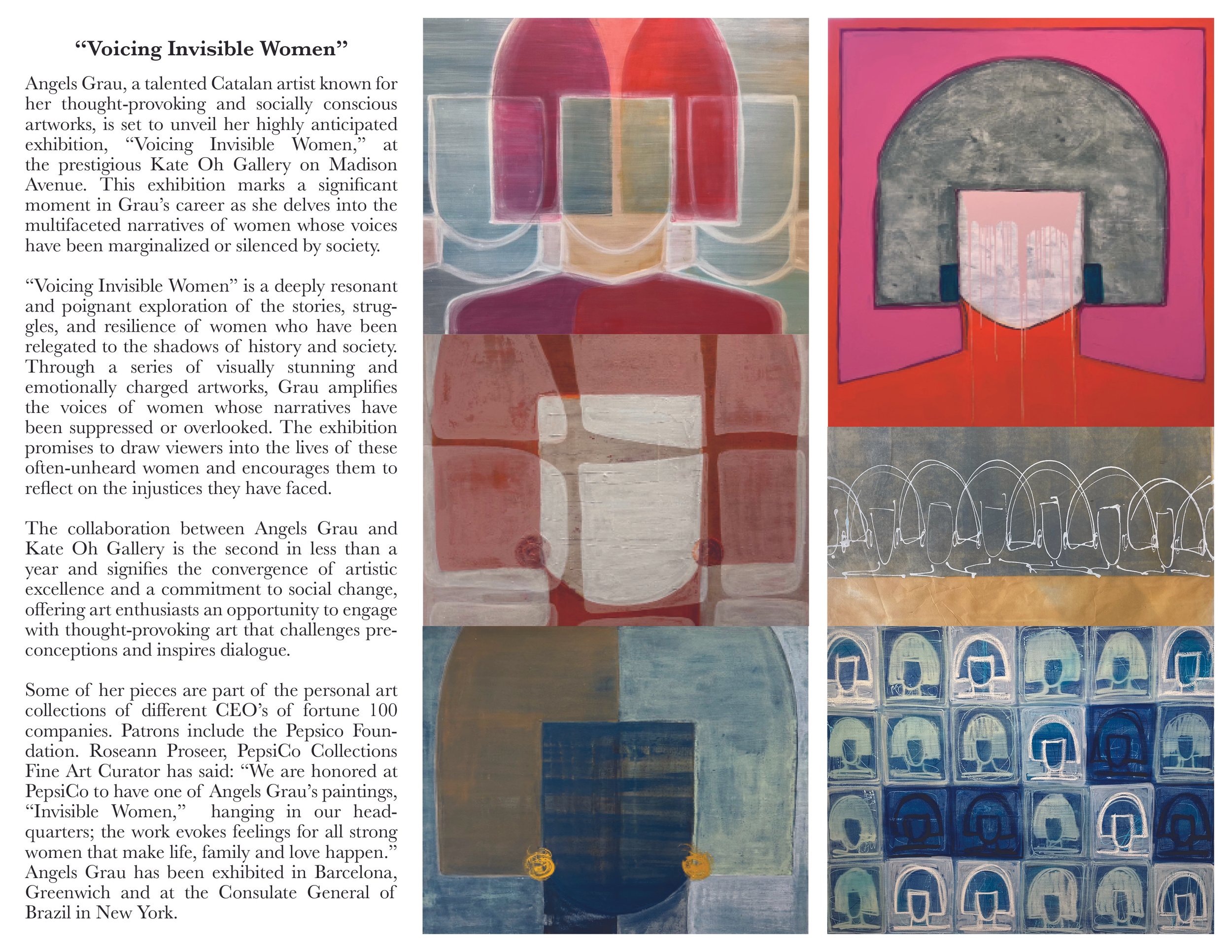

”Voicing Invisible Women”

by Angels Grau

October 3 - 22, 2023

“The Lyricism of Organic Tradition”

by Kim Gyoungmin

August 24 - September 30, 2023

“The Lyricism of Organic Tradition”

by Kwon Chigyu

August 24 - September 30, 2023

“Stone Wave”

by Jung Kwangsik

July 16 - August 19, 2023

“KIMONO REBORN” by Mayuko Okada

Exhibition Dates: May 30- June 23rd, 2023

“Tactile Effects” by Mague Brewer

Date: May 16 - 27, 2023

Rinaldo Skalamera

Exhibition Dates: April 16 - 30th, 2023

Callie Danae Hirsch

Exhibition: April 4th 15th, 2023

Moonlit Dream, Oil on Canvas 51 x 64”

“Collect Brazilian Jewelry”

Brazilian Handmade Jewelry

Exhibition Date: March 16 - April 1, 2023

“New York K-Art Festival”

Exhibition Date: March 4-12, 2023

“Flow”

by Insoo Chun

Exhibition Dates: February 19 - March 3, 2023

Read More here>>>

“Lucky Charm” (Dancheong)

by Kate Oh Trabulsi

Exhibition Dates: Jan 21 - 31, 2023

“Emptying and Filling”

by Kwan-Jin Oh

Exhibition Date: January 3-20, 2023

UES Minhwa (Korean Folk Traditions) Exhibition

Exhibition Date: Dec 20-30th,2022

Reception: Dec 23rd, 3-6PM

“Populist Animals”

by Heemin Moon

Exhibition Date: Dec 6-18th, 2022

Reception: Dec 6th, 6-8PM

https://www.meer.com/kateohgallery/en/news/71541

“INFINITELY REPELLING ORBS”

by Marko Stout

Opening: Dec 1st, 2022

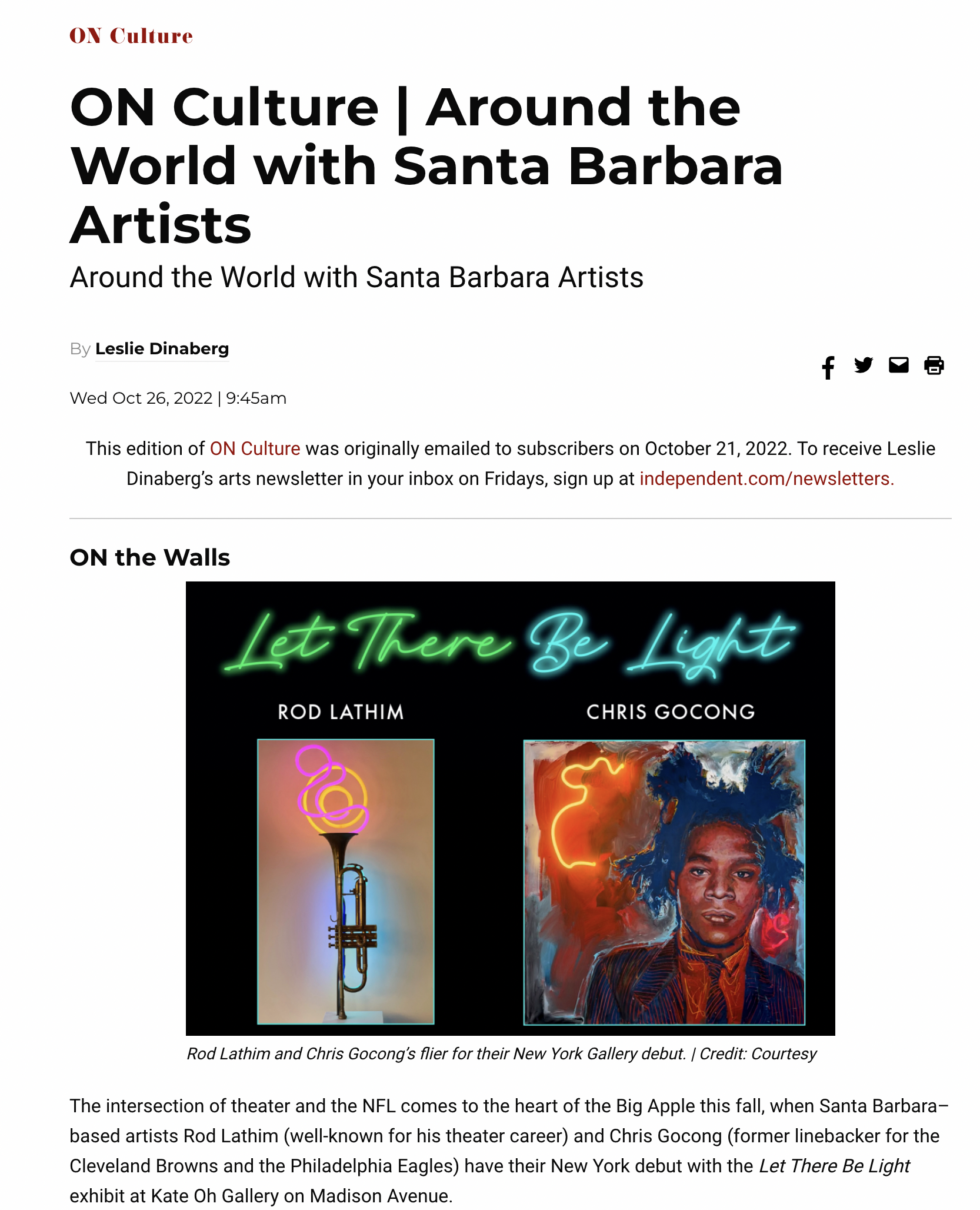

“Let There Be Light”

by Chris Gocong and Rod Lathim

Exhibition Dates: Nov. 3-25 2022

The talented artist Anely Girondin who exhibited at Kate Oh Gallery from

August 28 - September 4, 2022

was featured on NY Daily News.

Read more on her work and this article here.

“Dusted Photographs”

by Peter Ha (Jaeyell)

Exhibition Dates: Oct. 20-30, 2022

"Serendipity”,

showcasing dramatic abstract works by artists

Angels Grau and Alberto Murillo

Exhibition Dates: October 2-8, 2022

An Artist Who Paints From the Heart: Yang SiYoung

Exhibition Dates: September 26 - October 1, 2022

“Expressionist Scenes of Harrow”

by Nancy Prager

A collection of 'configurations' suggesting and mirroring haunting messages.

Exhibition Dates: September 6 - September 23, 2022

“The Movements of Our Roots”

by Anely Girondin

Exhibition Dates: August 28 - September 4

“Matrixes Small Works”

“HYPNOTIQ”

“The Pursuit of Happiness”

“The Lost Flame, Regained”

“ Cancer Fundraiser Show”

“Cancer Fundraiser Show” by Richard Volpe, Eliza Bender, and Alyssa Giammona.

Exhibition Date May 19 - 29, 2022

Closing Reception : Thursday May 26, 6 - 8 PM

Kate Oh Gallery is participating in the Madison Avenue Spring Gallery Walk on Saturday, May 14th, 2022. We cordially invite you to join us at the artist talk at 2 PM.

You can RSVP here: https://madisonavenuebid.org/springgallerywalk/

In this Gallery Walk, artist Bong Jung Kim's solo exhibition, Convalescence, will be on view. We invite you to his world of art and creativity merged with salutary perspectives.

"Convalescence”

"Convalescence"

by Bong Jung Kim, curated by Iris Inhee Moon

Kate Oh Gallery invites you to a Bong Jung Kim’s world of oriental philosophy merged with western aesthetics. Kim’s art explores a philosophical relationship and quest to the subject matter of love, desire, and longing, bridging the gesture and expression of his body and soul.

“TO BECOME LIFE": Two-Person Show

Irina Rodnikoff, Transition I

Miroslav Duzinkevich, Musicians

“Love Walk in New York”

Rainbow Group Show

Pema Rinzin, Peace and Energy (Yellow), 41 x 61 in.

Lori LaMont, La Premiere, 51 x 72 in. (framed)

"The Korean Archetype”

"The Korean Archetype" by Miky (Yoohyun) Kim at Kate Oh Gallery

Exhibition Date: March 1 -11, 2022

“Pop Art Figures: Present and Past”

Bong Jung Kim, Poppy Series

Encore Show: “Flower Dance”

#2 Flower Dance_64 x 52 inch _Mixed media_2021

Rosalyn Engelman

“Immortal Poets” 78 x 80 in, Acrylic on canvas

Pietro Antonio Narducci (1915-1999)

“Stone Wave”

51.2 X 23.6 X 0.79 in

“REQUIEM”

“Flower Dance”

“Flower Dance” by Bum Hun Lee Mixed Media, 2021 Size: 116.92 X 59.05 Inch

“Healing in City”

First Exhibition in our New Location

“America The Beautiful”

In the Present Tense

Iliya Mirochnik, By the Channel

James Sondow

by James Sondow and Iliya Mirochnik

The Birth of Oopsy and Oopsy

Elementals

Temptress, 2016, 60 x 48 in.

![프로처럼. [man]14x14x35(h)cm. [woman] 14x14x34(h)cm. acyrlic on rboze, marble. 2022. 각 120만원 (5).jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/59404fd8e3df288fc6563337/1691783391101-FMBW6AFHKBBV9G07E0QM/%E1%84%91%E1%85%B3%E1%84%85%E1%85%A9%E1%84%8E%E1%85%A5%E1%84%85%E1%85%A5%E1%86%B7.+%5Bman%5D14x14x35%28h%29cm.+%5Bwoman%5D+14x14x34%28h%29cm.+acyrlic+on+rboze%2C+marble.+2022.+%E1%84%80%E1%85%A1%E1%86%A8+120%E1%84%86%E1%85%A1%E1%86%AB%E1%84%8B%E1%85%AF%E1%86%AB+%285%29.jpg)